The Angel of History. The Angel of History: Walter Benjamin’s Vision of Hope and Despair by Raymond Barglow Published in "Tikkun Magazine," November 1998 A Klee drawing named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating.

His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. . — Walter Benjamin, Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History For Walter Benjamin, a German Jewish literary critic and philosopher writing in 1940, the very notion of “historical progress” was a cruel illusion. In Germany in the years between the two world wars, despair affected many of Benjamin’s contemporaries too. “Melancholy” is no longer the most common way of referring to the condition of those who view life as no longer worth living. But DNA is not the only way in which our lives are interwoven, for despondency and despair correlate with what goes on in the social world. Demonstration in front of the House of Representatives in Berlin. Anselm Kiefer. Art is a spiritual occupation, capturing a form of contact that science can’t: “It makes a connection between things that are separated,” Kiefer argues.

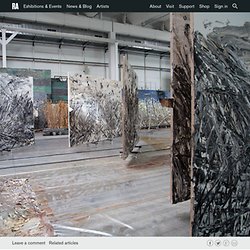

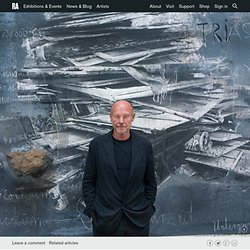

In his mind, his works should continually evolve and be fluid. The process of creating is of utmost importance to him, as it is the process rather than the end that has his interest, and what’s between the paintings rather than in them. “I am a dinosaur – I paint myself,” he comments. Kiefer argues that history is a material, which is moldable like argil, and in this way becomes less horrific as it is possible to reform it. “History shows that humankind has a wrong construction in their head… it’s badly done,” he continues, half-jokingly remarking that if an airplane had such a construction, it would fall down all the time. Anselm Kiefer (born 1945) is a German painter and sculptor. Anselm Kiefer was interviewed by Tim Marlow at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in 2010. Supported by Nordea-fonden. Royal Academy of Arts. Ruins, as a matter of fact, were exactly where Kiefer started.

He was born on 8 March 1945, just two months before V.E day. His arrival in the world therefore corresponded with the beginning of the postwar era; and – equally relevant to his development as an artist – he grew up among the debris of saturation bombing. A few years ago, he told me how he had been powerfully affected by that beginning. “I was born in ruins. So as a child I played in ruins, it was the only place.

This is Kiefer’s fundamental beginning, aesthetically and emotionally: his life started after a cataclysm. Unearthing that hidden past was one of his first undertakings as an artist. Beuys was an occasional mentor of Kiefer’s, though not a formal teacher. Anselm Kiefer: A beginner's guide. Kiefer’s work is not limited to painting or photography, but includes sculpture and installation on a vast scale.

In 1992, Kiefer moved his studio from Germany to Barjac in southern France. Not only did the landscape – in the form of sunflowers – seep into his work, but his work also had a major impact upon the landscape. Kiefer transformed 35 hectares of derelict industrial land into a gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – that includes archives, installations, storerooms, underground chambers, and huge concrete towers (two of which were here in the RA courtyard back in 2007). Kiefer has since relocated to the outskirts of Paris (it took 110 lorries to do the move) while Barjac remains. Tim Marlow, the RA’s Director of Artistic Programmes, likened it to “an ancient civilisation that has declined and been rediscovered.” Inside Anselm Kiefer's astonishing 200-acre art studio. Anselm Kiefer is a bewildering artist to get to grips with.

The word that comes up most often when his work is discussed is the heart-sinking and slippery "references". His vast pictures, thick with paint and embedded with objects from sunflowers and diamonds to lumps of lead, nod to the Nazis and Norse myth, to Kabbalah and the Egyptian gods, to philosophy and poetry, and to alchemy and the spirit of materials. How is one to unpick such a complex personal cosmology? Kiefer himself refuses to help: "Art really is something very difficult," he says. "It is difficult to make, and it is sometimes difficult for the viewer to understand … A part of it should always include having to scratch your head. " Now 69, Kiefer is the subject of a retrospective at the Royal Academy, where he is an honorary academician and which, through its summer exhibitions, has done much to bring him to the attention of the British public.

Kiefer is a great revisitor of themes. Such mutability fascinates him.