Liber AL vel Legis. Ancient Egyptian religion. Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world.

The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments. The details of these sacred events differ greatly from one text to another and often seem contradictory. Egyptian myths are primarily metaphorical, translating the essence and behavior of deities into terms that humans can understand.

Mythology profoundly influenced Egyptian culture. Origins[edit] The development of Egyptian myth is difficult to trace. Another possible source for mythology is ritual. Definition and scope[edit] Content and meaning[edit] Sources[edit] Celtic mythology. Overview[edit] Though the Celtic world at its apex covered much of western and central Europe, it was not politically unified nor was there any substantial central source of cultural influence or homogeneity; as a result, there was a great deal of variation in local practices of Celtic religion (although certain motifs, for example the god Lugh, appear to have diffused throughout the Celtic world).

Inscriptions of more than three hundred deities, often equated with their Roman counterparts, have survived, but of these most appear to have been genii locorum, local or tribal gods, and few were widely worshipped. However, from what has survived of Celtic mythology, it is possible to discern commonalities which hint at a more unified pantheon than is often given credit. Chinese mythology. Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China: these include myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups (of which fifty-six are officially recognized by the current administration of China).[1] Chinese mythology includes creation myths and legends, such as myths concerning the founding of Chinese culture and the Chinese state.

As in many cultures' mythologies, Chinese mythology has in the past been believed to be, at least in part, a factual recording of history. Thus, in the study of historical Chinese culture, many of the stories that have been told regarding characters and events which have been written or told of the distant past have a double tradition: one which presents a more historicized and one which presents a more mythological version.[2] Epic of Gilgamesh. The Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem from Mesopotamia, is considered the world's first truly great work of literature.

The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian poems about 'Bilgamesh' (Sumerian for 'Gilgamesh'), king of Uruk. These independent stories were used as source material for a combined epic. The first surviving version of this combined epic, known as the "Old Babylonian" version, dates to the 18th century BC and is titled after its incipit, Shūtur eli sharrī ("Surpassing All Other Kings"). Only a few tablets of it have survived. The later "Standard" version dates from the 13th to the 10th centuries BC and bears the incipit Sha naqba īmuru ("He who Saw the Deep", in modern terms: "He who Sees the Unknown").

Essay: Storytelling, the Meaning of Life, and The Epic of Gilgamesh. Fengshen Yanyi. Fengshen Yanyi, also known as Fengshen Bang, or translated as The Investiture of the Gods, is a 16th-century Chinese novel and one of the major vernacular Chinese works in the shenmo genre written during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).[1] Consisting of 100 chapters, it was first published in book form around the 1550s.[1] Plot[edit] The novel is a romanticised retelling of the overthrow of King Zhou, the last ruler of the Shang Dynasty, by King Wu, who would establish the Zhou Dynasty in place of Shang.

The story integrates oral and written tales of many Chinese mythological figures who are involved in the struggle as well. These figures include human heroes, immortals and various spirits (usually represented in avatar form like vixens, and pheasants, and sometimes inanimate objects such as a pipa). Some well-known anecdotes[edit] Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh (/ˈɡɪl.ɡə.mɛʃ/; Akkadian cuneiform: 𒄑𒂆𒈦 [𒄑𒂆𒈦], Gilgameš, often given the epithet of the King, also known as Bilgamesh in the Sumerian texts)[1] was the fifth king of Uruk, modern day Iraq (Early Dynastic II, first dynasty of Uruk), placing his reign ca. 2500 BC.

According to the Sumerian King List he reigned for 126 years. Marduk. Mesopotamian religion. The god Marduk and his dragon Mušḫuššu Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices followed by the Sumerian and East Semitic Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian and later migrant Arameans and Chaldeans, living in Mesopotamia (a region encompassing modern Iraq, Kuwait, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria) that dominated the region for a period of 4200 years from the fourth millennium BCE throughout Mesopotamia to approximately the 10th century CE in Assyria.[1] Mesopotamian polytheism was the only religion in ancient Mesopotamia for thousands of years before entering a period of gradual decline beginning between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE.

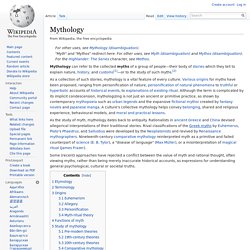

Reconstruction[edit] Myth of Osiris and Isis. From right to left: Isis, her husband Osiris, and their son Horus, the protagonists of the Osiris myth, in a Twenty-second Dynasty statuette The Osiris myth reached its basic form in or before the 24th century BCE.

Many of its elements originated in religious ideas, but the conflict between Horus and Set may have been partly inspired by a regional struggle in Egypt's early history or prehistory. Mythology. Some (recent) approaches have rejected a conflict between the value of myth and rational thought, often viewing myths, rather than being merely inaccurate historical accounts, as expressions for understanding general psychological, cultural or societal truths.

Etymology[edit] The English term mythology predates the word myth by centuries.[5] It appeared in the 15th century,[7] borrowed whole from Middle French mythologie. The word mythology "exposition of myths" comes from Middle French mythologie, from Late Latin mythologia, from Greek μυθολογία mythologia "legendary lore, a telling of mythic legends; a legend, story, tale," from μῦθος mythos "myth" and -λογία -logia "study. Nuada Airgetlám. In Irish mythology, Nuada or Nuadu (modern spelling: Nuadha), known by the epithet Airgetlám (modern spelling: Airgeadlámh, meaning "silver hand/arm"), was the first king of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

He is cognate with the Gaulish and British god Nodens. His Welsh equivalent is Nudd or Lludd Llaw Eraint. Description[edit] Nuada was king of the Tuatha Dé Danann for seven years before they came to Ireland. Sumerians. The Dagda. Description[edit] Despite his great power and prestige, the Dagda is sometimes depicted as oafish and crude, even comical, wearing a short, rough tunic that barely covers his rump, dragging his great penis on the ground.[1] Such features are thought to be the additions of Christian redactors for comedic purposes. Tellingly, the Middle Irish language Coir Anmann (The Fitness of Names) paints a less clownish picture: "He was a beautiful god of the heathens, for the Tuatha Dé Danann worshipped him: for he was an earth-god to them because of the greatness of his (magical) power. "[2]