Four Reasons You Need Silence. How Playing Music Benefits Your Brain More than Any Other Activity. “Each note rubs the others just right, and the instrument shivers with delight.

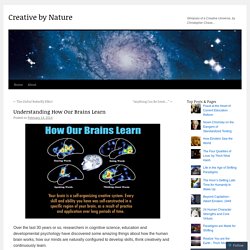

The feeling is unmistakable, intoxicating,” musician Glenn Kurtz wrote in his sublime meditation on the pleasures of practicing, adding: “My attention warms and sharpens… Making music changes my body.” Kurtz’s experience, it turns out, is more than mere lyricism — music does change the body’s most important organ, and changes it more profoundly than any other intellectual, creative, or physical endeavor. This short animation from TED-Ed, written by Anita Collins and animated by Sharon Colman Graham, explains why playing music benefits the brain more than any other activity, how it impacts executive function and memory, and what it reveals about the role of the same neural structure implicated in explaining Leonardo da Vinci’s genius.

Breaking the Code: Why Yuor Barin Can Raed Tihs. By Natalie Wolchover You might not realize it, but your brain is a code-cracking machine.

For emaxlpe, it deson’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod aepapr, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer are in the rghit pcale. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit pobelrm. Passages like these have been bouncing around the Internet for years. But how do we read them? According to Marta Kutas, a cognitive neuroscientist and the director of the Center for Research in Language at the University of California, San Diego, the short answer is that no one knows why we’re so good at reading garbled nonsense. Understanding How Our Brains Learn. Over the last 30 years or so, researchers in cognitive science, education and developmental psychology have discovered some amazing things about how the human brain works, how our minds are naturally configured to develop skills, think creatively and continuously learn.

You’ve probably heard that we each use only about 10% of our brains. That’s not quite accurate. Actually, while we probably use less than 40% of the brain at any given moment, the patterns and regions of activation shift continuously throughout the day. These PET scans (above) can help to make this discovery easier to understand. How Does the Brain Learn Best? Smart Studying Strategies. In his new book, “How We Learn: The Surprising Truth about When, Where, and Why It Happens,” author Benedict Carey informs us that “most of our instincts about learning are misplaced, incomplete, or flat wrong” and “rooted more in superstition than in science.” That’s a disconcerting message, and hard to believe at first. But it’s also unexpectedly liberating, because Carey further explains that many things we think of as detractors from learning — like forgetting, distractions, interruptions or sleeping rather than hitting the books — aren’t necessarily bad after all.

They can actually work in your favor, according to a body of research that offers surprising insights and simple, doable strategies for learning more effectively. Society has ingrained in us “a monkish conception of what learning is, of you sitting with your books in your cell,” Carey told MindShift. “How We Learn” presents a new view that takes some of the pressure off. Getting to Know Your Brain’s Memory Processes. These games may improve psychopath behavior. People with psychopathy tend not to feel fear, consider the emotions of others, or reflect on their behavior—and these traits make them notoriously difficult to treat.

A new study to appear in Clinical Psychological Science suggests it may be possible to teach psychopaths to consider emotion and other pieces of information when they make decisions. The results could form the basis of treatment for this group of dangerous prisoners—7 of 10 of whom go on to commit new crimes after being released. “They are also the world’s worst multi-taskers and tend not to process information, such as pain and suffering of others, when they are engaging in criminal acts,” says Arielle Baskin-Sommers, a psychologist at Yale University.

Psychopaths ignore information that is important to stop antisocial behavior, she notes. 'Molecular madness' in brain after blast injury. U.

PITTSBURGH (US) — Exposure to a blast can cause changes in the brain that resemble patterns seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Blast-induced traumatic brain injury (TBI) has become an important issue in combat casualty care. In many cases of mild TBI, MRI scans and other conventional imaging technology don’t show overt damage. “Our research reveals that despite the lack of a lot of obvious neuronal death, there is a lot of molecular madness going on in the brain after a blast exposure,” says Patrick Kochanek, professor and vice chair of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. Brain ‘speed’ linked to psychosis risk. CARDIFF U.

(UK) — Children whose brains process information more slowly than those of their peers are at greater risk of psychotic experiences, according to new research. Psychotic experiences can include hearing voices, seeing things that are not present, or holding unrealistic beliefs that other people don’t share. Reward sets off ruckus in teen brain. U.

PITTSBURGH (US) — The frenzy of neuron activity seen in adolescent rat brains when reward is on the line suggests a biological root to risky behavior in teenagers. The findings, reported in the Journal of Neuroscience, also may explain why adolescents are more vulnerable to drug addiction, behavioral disorders, and other psychological ills. Electrode recordings of adult and adolescent brain-cell activity during the performance of a reward-driven task show that adolescent brains react to rewards with far greater excitement than adult brains. This frenzy of stimulation occurred with varying intensity throughout the study along with a greater degree of disorganization in adolescent brains. Brain’s flexibility predicts learning. UC SANTA BARBARA/UNC-CHAPEL HILL (US) — How flexible the brain is can be used to determine a person’s capacity for future learning.

A brain’s flexibility is determined by how different areas of the brain link up in different combinations. “What we wanted to do was find a way to predict how much someone is going to learn in the future, independent of how they are as a performer,” says Scott T. Grafton, professor of psychology at University of California, Santa Barbara and senior author of a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers collected brain imaging data from people performing a motor task, and then analyzed the data using new computational techniques. For the three-session study, 18 volunteers had to push a series of buttons, similar to a sequence of notes on a piano keyboard, as fast as possible. Brainwaves show how sleep boosts visual learning. Trained to spot hidden patterns, volunteers show a significant increase in sigma brainwave power during sleep, suggesting sleep locks in learning, researchers say.

The new study, led by Ji Won Bang, a Brown University graduate student, was presented this month at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in San Diego. It builds off earlier research reported in the Journal of Neuroscience that two specific frequencies, fast-sigma and delta, that operate in the supplementary motor area of the brain were directly associated with learning a finger-tapping task akin to typing or playing the piano. The new results show something similar with a visual task in which 15 volunteers were trained to spot a hidden texture amid an obscuring pattern of lines. Children's sleep quality matters for school. A new study finds a link between a good night’s sleep for school-aged kids and better performance in math and languages—subjects that are powerful predictors of later learning and academic success.

In the journal Sleep Medicine, the researchers reported that “sleep efficiency” is associated with higher academic performance in those key subjects. Sleep efficiency is a gauge of sleep quality that compares the amount of actual sleep time with the total time spent in bed. While other studies have pointed to links between sleep and general academic performance, the scientists examined the impact of sleep quality on report-card grades in specific subjects. 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain. New findings on how the ear hears could lead to better hearing aids. A healthy ear is much better at detecting and transmitting sound than even the most advanced hearing aid. But now researchers reporting in the August 20 issue of the Biophysical Journal, a Cell Press publication, have uncovered new insights into how the ear—in particular, the cochlea—processes and amplifies sound.

The findings could be used for the development of better devices to improve hearing. How sleep helps brain learn motor task. Sleep helps the brain consolidate what we've learned, but scientists have struggled to determine what goes on in the brain to make that happen for different kinds of learned tasks. In a new study, researchers pinpoint the brainwave frequencies and brain region associated with sleep-enhanced learning of a sequential finger tapping task akin to typing, or playing piano. PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — You take your piano lesson, you go to sleep and when you wake up your fingers are better able to play that beautiful sequence of notes. Disease caused by repeat brain trauma in athletes may affect memory, mood, behavior.

New research suggests that chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain disease associated with repeat brain trauma including concussions in athletes, may affect people in two major ways: initially affecting behavior or mood or initially affecting memory and thinking abilities. The study appears in the August 21, 2013, online issue of Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. CTE has been found in amateur and professional athletes, members of the military and others who experienced repeated head injuries, including concussions and subconcussive trauma.

"This is the largest study to date of the clinical presentation and course of CTE in autopsy-confirmed cases of the disease," said study author Robert A.