If Climate Didn't Doom Neanderthals, Did Humans? Neanderthals could handle the weather, but they couldn’t handle us, concludes a new analysis of late-Pleistocene hominid habitation.

Soon after modern humans arrived in Western Europe, plenty of temperate, food-rich habitat existed for our evolutionary near-brothers — but their settlements dwindled, and modern human settlements spread. These patterns suggest that one of modern anthropological history’s great mysteries had a harsh ending: a competition in which Neanderthals, for reasons still unknown, were doomed. "Neanderthals didn’t end up being the champion lineage that emerged from the end of the Pleistocene," said study co-author A.

Townsend Peterson, a Kansas University evolutionary biologist. "Wouldn’t it be fascinating to understand that weird point in human history, when there were two lineages of Homo, in the same region? " One popular explanation holds that climate changes were inhospitable to Neanderthals unable to keep pace with fluctuations in food and weather. See Also: Fossil Finger DNA Points to New Type of Human. Continued study of an approximately 40,000 year old finger bone from Siberia has identified a previously unknown type of human — one that may have interbred with the ancestors of modern-day Melanesian people.

The fossil scrap — just the tip of a juvenile female’s finger — was discovered in 2008 during excavations of Denisova cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. Anatomically, it looks like it could have belonged to a Neanderthal or a modern human. But, in an initial announcement published in April in Nature, a team of scientists led by geneticist Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology concluded the bone belonged to a distinct population of humans that last shared a common ancestor with Neanderthals and our species about a million years ago.

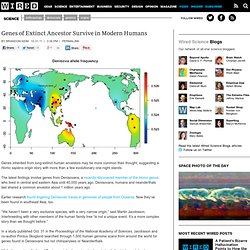

The new study, published by Pääbo and colleagues Dec. 22 in Nature, provides further evidence that Denisova cave was home to unique humans. The big question, however, is whether the Denisovans are a new species of human. Genes of Extinct Ancestor Survive in Modern Humans. Genes inherited from long-extinct human ancestors may be more common than thought, suggesting a Homo sapiens origin story with more than a few evolutionary one-night stands.

The latest findings involve genes from Denisovans, a recently-discovered member of the Homo genus who lived in central and eastern Asia until 40,000 years ago. Denisovans, humans and neanderthals last shared a common ancestor about 1 million years ago. Earlier research found lingering Denisovan traces in genomes of people from Oceania. Now they’ve been found in southeast Asia, too. “We haven’t been a very exclusive species, with a very narrow origin,” said Martin Jacobsson. In a study published Oct. 31 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jacobsson and co-author Pontus Skoglund searched through 1,500 human genome scans from around the world for genes found in Denisovans but not chimpanzees or Neanderthals. The 40,000 year-old tooth from which Denisovans were first identified in 2010. See Also: Neanderthal Genome Shows Most Humans Are Cavemen. After years of anticipation, the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced.

It’s not quite complete, but there’s enough for scientists to start comparing it with our own. According to these first comparisons, humans and Neanderthals are practically identical at the protein level. Whatever our differences, they’re not in the composition of our building blocks. However, even if the Neanderthal genome won’t show scientists what makes humans so special, there’s a consolation prize for the rest of us. Most people can likely trace some of their DNA to Neanderthals. “The Neanderthals are not totally extinct. It took four years for Pääbo’s team to assemble a working sequence from DNA in the bones of three 38,000-year-old Neanderthal women, found in Croatia’s Vindija Cave. Though much remains unfinished, researchers were able to compare the Neanderthal genome to the human at 14,000 protein-coding gene segments that differ between humans and chimpanzees. Images: 1. See Also: