Voices from Chernobyl, Svetlana Alexievich. On April 26, 1986, at 1:23:58 a. m., a series of explosions destroyed the reactor in the building that housed Energy Block #4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station.

The catastrophe at Chernobyl became the largest technical disaster of the twentieth century. . . . For tiny Belarus (population: ten million), it was a national disaster. . . . Today, one out of every five Belarussians lives on contaminated land. This amounts to 2.1 million people, of whom seven hundred thousand are children. In the Gomel and Mogilev regions, which suffered the most from Chernobyl, mortality rates exceed birthrates by twenty percent. —Belaruskaya entsiklopedia, 1996, s.v. On April 29, 1986, instruments recorded high levels of radiation in Poland, Germany, Austria, and Romania. —“The Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident in Belarus” The Sakharov International College on Radioecology, Minsk, 1992 Lyudmilla Ignatenko Wife of deceased Fireman Vasily Ignatenko We were newlyweds.

One night I heard a noise. Svetlana Alexievich: ′Reality has always attracted me like a magnet′ If there ever was a stark manifesto of intent, it came with Svetlana Alexievich's debut novel "War's Unwomanly Face.

" Released in 1985 and set during World War II, the novel ties together a series of moving and often stark monologues on the brutality and hopelessness of war - all told by women and children. Alexievich made no illusions: she was going to toe no one else's line. For those new to Alexievich's work, the Swedish Academy has recommended starting by reading that "War's Unwomanly Face. " The innovative writer has "mapped the soul" of the Soviet and post-Soviet people, said the Academy. The Nobel Prize is presented to Alexievich in a ceremony in Stockholm on Thursday (10.12.2015), the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death. First-hand account of Soviet Union's disintegration It's her audacious determination to tell such brutally real stories that had Alexievich on the run for a decade. Who inspired the Nobel Prize winner?

Alexievich invented a 'new genre' Writing for Peace: How Mighty is the Pen? Svetlana Alexievich, The Dostoevsky of Nonfiction. Another of Alexievich’s clear influences is Dostoevsky, whom she mentions often.

She shares his belief that compassion is the greatest hope for humankind, and his rejection of the cycles of revenge that have dictated so much of human history. Like Dostoevsky, Alexievich uses seemingly artless prose, littered with ellipses, to give us truth, conveyed through the gathering strength of many voices. Like Dostoevsky, Alexievich is concerned not only with national realities, but with universal human values. It will be a pity if she is understood as a strictly anti-Soviet or anti-totalitarian writer.

Although her work paints a lovingly detailed picture of Soviet and post-Soviet reality, her concerns transcend historical particularities. Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, starts with Alexievich not wanting to write about war. She doesn’t want to write about war again, but she must. Svetlana Alexievich, Nobel Laureate. “Please bring the lady one green tea,” went the request.

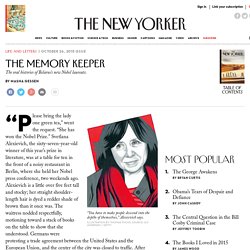

“She has won the Nobel Prize.” Svetlana Alexievich, the sixty-seven-year-old winner of this year’s prize in literature, was at a table for ten in the front of a noisy restaurant in Berlin, where she held her Nobel press conference, two weekends ago. Alexievich is a little over five feet tall and stocky; her straight shoulder-length hair is dyed a redder shade of brown than it once was. The waitress nodded respectfully, motioning toward a stack of books on the table to show that she understood. Germans were protesting a trade agreement between the United States and the European Union, and the center of the city was closed to traffic. This year’s literature Nobel is the first to be awarded to a writer who works exclusively with living people. At the morgue they said, “Want to see what we’ll dress him in?” Alexievich told me, “We live in an environment of banality. I am walking with Vladya. . . .

Is this something I can talk about?