Polyphasic sleep. Vasil Levski. Vasil Levski[1] (Bulgarian: Васил Левски, originally spelled Василъ Лѣвскій,[2] pronounced [vɐˈsiɫ ˈlɛfski]), born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev[3] (Васил Иванов Кунчев; 18 July 1837 – 18 February 1873), was a Bulgarian revolutionary and a national hero of Bulgaria.

Dubbed the Apostle of Freedom, Levski ideologised and strategised a revolutionary movement to liberate Bulgaria from Ottoman rule. Founding the Internal Revolutionary Organisation, Levski sought to foment a nationwide uprising through a network of secret regional committees. Born in the Sub-Balkan town of Karlovo to middle class parents, Levski became an Orthodox monk before emigrating to join the two Bulgarian Legions in Serbia and other Bulgarian revolutionary groups. Epicurus. Epicurus (/ˌɛpɪˈkjʊərəs/ or /ˌɛpɪˈkjɔːrəs/;[2] Greek: Ἐπίκουρος, Epíkouros, "ally, comrade"; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher as well as the founder of the school of philosophy called Epicureanism.

Only a few fragments and letters of Epicurus's 300 written works remain. Much of what is known about Epicurean philosophy derives from later followers and commentators. Zeno's paradoxes. Zeno's arguments are perhaps the first examples of a method of proof called reductio ad absurdum also known as proof by contradiction.

They are also credited as a source of the dialectic method used by Socrates.[3] Some mathematicians and historians, such as Carl Boyer, hold that Zeno's paradoxes are simply mathematical problems, for which modern calculus provides a mathematical solution.[4] Some philosophers, however, say that Zeno's paradoxes and their variations (see Thomson's lamp) remain relevant metaphysical problems.[5][6][7] The origins of the paradoxes are somewhat unclear.

Diogenes Laertius, a fourth source for information about Zeno and his teachings, citing Favorinus, says that Zeno's teacher Parmenides was the first to introduce the Achilles and the tortoise paradox. But in a later passage, Laertius attributes the origin of the paradox to Zeno, explaining that Favorinus disagrees.[8] Axial Age. Axial Age or Axial Period (Ger.

Achsenzeit, "axis time") is a term coined by German philosopher Karl Jaspers to describe the period from 800 to 200 BC, during which, according to Jaspers, similar revolutionary thinking appeared in Persia, India, China and the Occident. The period is also sometimes referred to as the Axis Age.[1] Jaspers, in his Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (The Origin and Goal of History), identified a number of key Axial Age thinkers as having had a profound influence on future philosophies and religions, and identified characteristics common to each area from which those thinkers emerged. Jaspers saw in these developments in religion and philosophy a striking parallel without any obvious direct transmission of ideas from one region to the other, having found no recorded proof of any extensive intercommunication between Ancient Greece, the Middle East, India, and China.

A pivotal age[edit] Free will. Though it is a commonly held intuition that we have free will,[3] it has been widely debated throughout history not only whether that is true, but even how to define the concept of free will.[4] How exactly must the will be free, what exactly must the will be free from, in order for us to have free will?

Historically, the constraint of dominant concern has been determinism of some variety (such as logical, nomological, or theological), so the two most prominent common positions are named incompatibilist or compatibilist for the relation they hold to exist between free will and determinism. In Western philosophy[edit] The underlying issue is: Do we have some control over our actions, and if so, what sort of control, and to what extent? These questions predate the early Greek stoics (for example, Chrysippus), and some modern philosophers lament the lack of progress over all these millennia.[11][12] Below are the classic arguments bearing upon the dilemma and its underpinnings. Free City of Danzig. The Free City of Danzig (German: Freie Stadt Danzig; Polish: Wolne Miasto Gdańsk) was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (today Gdańsk) and nearly 200 towns in the surrounding areas.

It was created on 15 November 1920[1][2] in accordance with the terms of Article 100 (Section XI of Part III) of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The Free City included the city of Danzig and other nearby towns, villages, and settlements that had been primarily inhabited by ethnic Germans. As the Treaty stated, the region was to remain separated from the nation of Germany and from the newly independent nation of Poland, but it was not an independent state.[3] The Free City was under League of Nations protection and put into a binding customs union with Poland. Since Poland still was not in complete control of the seaport, especially regarding military equipment, a new seaport was built in nearby Gdynia, beginning 1921. Federation. A map displaying current official federations.

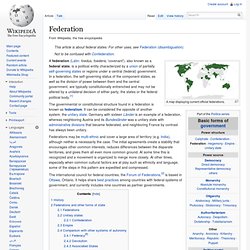

A federation (Latin: foedus, foederis, 'covenant'), also known as a federal state, is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions under a central (federal) government. In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, are typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body.[1] Tribe. There are an estimated one hundred and fifty million tribal individuals worldwide,[2] constituting around forty percent of indigenous individuals.

Although nearly all tribal people are indigenous, some are not indigenous to the areas where they now live. The distinction between tribal and indigenous is important because tribal peoples have a special status acknowledged in international law. They often face particular issues in addition to those faced by the wider category of indigenous peoples.