Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare. An introduction to Shakespeare’s comedy. John Mullan considers the key characteristics of Shakespeare's varied comedies, but he also considers the ways the playwright mixes genres by bringing comedy into his tragedies and tragedy into his comedies. When the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, the First Folio, was published in 1623, its contents page divided them into three categories: Comedies, Histories and Tragedies. The list of Comedies included Measure for Measure and The Merchant of Venice, plays that modern audiences and readers have not found particularly ‘comic’. Also included were two late plays, The Tempest and The Winter’s Tale, that critics often now classify as ‘Romances’.

If we ask ourselves what these four plays have in common with those such as As You Like It or Twelfth Night, which we are used to calling ‘comedies’, the answer gives us a clue to the meaning of ‘comedy’ for many of Shakespeare’s educated contemporaries. All of them end in marriage (or at least betrothal). Contextual summary of Much Ado About Nothing. Essential knowledge and literary terms for understanding Shakespeare. An Award winning.

You - you- your- your formal and distant form of address suggesting respect for a superior or courtesy to a social equal.

Thou - thee - thy - thine informal and close form and can imply either closeness or contempt. Gertrude: Hamlet, thou hast thy father much offended. Hamlet: Mother, you have my father much offended. Gertrude: Come, come, you answer with an idle tongue. Hamlet: Go, go, you question with a wicked tongue. "Ye/you" or "thou/thee" sometimes show social classes, too. Falstaff: Dost thou hear, hostess? It can be insulting if it was used by an inferior to address a superior social rank. 5 facts about marriage, love, and sex in Shakespeare's England.

Considering the many love affairs, sexual liaisons, and marriages that occur in Shakespeare’s plays, how many of them accurately represent their real-life counterparts?

Genuine romantic entanglements certainly don’t work out as cleanly as the ending of Twelfth Night, where Sebastian and Olivia, Duke Orsino and Viola, and Toby and Maria all wind up as married couples. However, Shakespeare’s imaginary theatrical arrangements frequently collided with significant thoughts and beliefs of 16th-century England, such as a woman’s duty as a wife and the social standing of “bastard” children. In the late 16th century, the legal age for marriage in Stratford was only 14 years for men and 12 years for women. Usually, men would be married between the ages of 20 and 30 years old. Alternatively, women were married at an average of 24 years old, while the preferred ages were either 17 or 21.Of Shakespeare’s eligible female characters who refuse marriage and husbands, not one of them remains single.

Much ado about quite a lot: gender, trickery and double standards in Shakespeare’s play. ‘O God, that I were a man!’

Cries Beatrice after her cousin, Hero, has been left at the altar on her wedding day. When Beatrice says this, what she means is that she wishes that, as a woman, she were entitled to the attributes that men are not only allowed to have, but are celebrated for. Qualities such as the ability to take personal revenge on men like Claudio, openly defy father-figures like Leonato, or even simply to fall in love with a person of her choosing and for her affection not to be seen as weakness, nor her sexual desires be used as evidence of her inconstant character. Much Ado About Nothing is a bit of a misleading title. Deception and dramatic irony in Much Ado About Nothing. Although the characters might be fooled by the many deceptions in the play, the audience seems to know better, but Andrea Varney suggests that our role as observers is more complex and uncertain.

In Much Ado About Nothing, Shakespeare sets up a fairy-tale contrast between two half-brothers – Don Pedro and the illegitimate Don John. As in many plays of this era, the ‘bastard’ is cast as the villain while Don Pedro, the Prince of Aragon, seems to be the reliable face of authority in Messina. Within this symmetrical structure, we might expect the good Prince to be open and honest, while Don John and his cronies will be duplicitous.

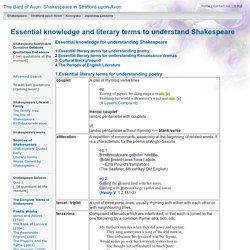

However, it soon becomes clear that deception and self-deception, visual and verbal confusion, are rife everywhere in Messina – from Don Pedro’s benevolent schemes to bring two pairs of lovers together, to Don John’s vindictive plots to pull them apart. A ‘plain-dealing villain’ and a disguised prince The masked ball: to ‘know me, and not know me’ ‘Trust no agent’ Shakespeare's Globe. A Glossary of Common Shakespearean Language.