The Longest Show Cave in England and the UK. Introduction to caving places. <p style="font-size:0.9em;"> Please enable Javascript on your browser so that the drop-down menus work or else use the <a href="..

/base/sitemap.php">website map</a>. Some external links on this site may not work without JavaScript enabled. </p> Where am I? Geological Society - Weathering Processes in Britain. Caves of South Wales. Mendip Cave Map. CaveMaps.org. Caves, subsidence and soluble rocks. Dissolution of soluble rocks produces landforms and features collectively known as 'karst'.

Britain has four main types of soluble or 'karstic' rocks each with a different character and associated potential hazards. Limestone Karst is most often seen in limestone, a rock made up mainly of calcium carbonate. Chalk Chalk is a very distinctive, pure form of limestone, and is the most widespread carbonate rock in the country. Gypsum Karst in gypsum (hydrated calcium sulphate) is present mainly in the Permian rocks of eastern and north-eastern England. Salt In Britain, salt (halite or sodium chloride) occurs mainly in the Permian and Triassic rocks of central and north-eastern England. Engineering problems Engineering problems associated with these karstic rocks include subsidence, sinkhole formation, uneven rock-head and reduced rock-mass strength.

It can be triggered by man-made disturbance of the ground, a change in drainage patterns, heavy rain or by water abstraction. Nottingham's Caves Database - Datasets. Caves and Caving in the UK. Designed by arb using Xara "When I try to imagine a faultless love Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.

"W.H. Auden, "In Praise of Limestone" Search A very simple search engine has been implemented allowing you to search the documents on this server. What's new Previous contents of What's new can be found on the What's Old page. These pages are maintained by Andrew Brooks <arb@sat.dundee.ac.uk> If you have any comments, corrections or suggestions, or would like me to put your documents on-line here then please e-mail me. Back to arb's home page. Cave Database. Cave Registry Data Archive. UK and Ireland cave lengths and depths. SAC selection - 8310 Caves not open to the public.

8310 Caves not open to the public Description and ecological characteristics Caves are formed by the erosion of soluble rocks, such as limestones.

They typically form the subterranean components of a distinctive ‘karst’ landscape, and are associated with various topographic features, including gorges, dry valleys, 8240 Limestone pavements, and dolines (surface depressions and hollows). Caves not open to the public is interpreted as referring to natural caves which are not routinely exploited for tourism, and which host specialist or endemic cave species or support important populations of Annex II species. Caves lack natural illumination, and therefore support species which are adapted to living in the dark. The cavernicolous flora and fauna of the UK and other parts of northern Europe is highly impoverished compared to southern Europe. Cavernicoles in the UK include bacteria, algae, fungi and various groups of invertebrates (e.g. insects, spiders and crustaceans).

Site accounts. River Wey & Navigations : The Legends of the Wey Valley. The Alchemist of Stoke Guildford had its very own alchemist who claimed he could turn base metals into gold.

James Higginbottom was left a fortune by his uncle upon his death in 1781. One of the conditions attached was that he change his name to Price, meaning that the now James Price in effect became in name his uncle. With his new money James bought a small country estate in Stoke, a village as it was then just to the north of Guildford. There he established his laboratory with the initial intention of dedicating his time to chemistry, a long-time hobby. In 1782 Price announced to an astonished world that he had discovered elements for making a catalyst, his very own Philosopher’s Stone, that could turn mercury into silver and gold. Price provided a sample to be tested which proved that the substances were indeed gold and silver.

Celtic Gods and Goddesses. (Pan-Celtic) [Loo] The Shining One; Sun God; God of War; "Many Skilled"; "Fair-Haired One"; "White or Shining"; a hero god.

His feast is Lughnassadh, a harvest festival. Associated with ravens. His symbol was a white stag in Wales. Son of Cian and Ethniu. Lugh had a magic spear and rod-sling. His sacred symbol was a spear. List of caves in the United Kingdom. This is a list of caves in the United Kingdom, including information on the largest and deepest caves in the UK.

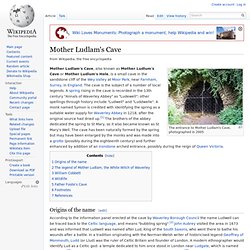

Longest and deepest[edit] The longest cave system in the UK is The Three Counties System in the Yorkshire Dales, with 86.6 km (53.8 mi) of passageways. It includes the Ease Gill system, the Notts Pot / Ireby Fell Cavern system, the Lost John's Cave system, and the Pippikin Pot system, all of which are connected.[1] The deepest cave in Wales and the UK is Ogof Ffynnon Ddu, 308 metres (1,010 ft) deep and containing around 50 km (31 mi) of passageways.The deepest cave in England is Peak Cavern in Speedwell Cavern, Derbyshire, 248 metres (814 ft) deep.The deepest cave in Scotland is Cnoc nan Uamh ('hill of the caves') in Assynt, 83 metres (272 ft) deep.The deepest cave in Northern Ireland is Reyfad Pot in County Fermanagh, 193 metres (633 ft) deep. England[edit] By English caving region. South Devon[edit] Mother Ludlam's Cave. The entrance to Mother Ludlam's Cave, photographed in 2005 Origins of the name[edit] According to the information panel erected at the cave by Waverley Borough Council the name Ludwell can be traced back to the Celtic language, and means "bubbling spring".[2] John Aubrey visited the area in 1673 and was informed that Ludwell was named after Lud, King of the South Saxons, who went there to bathe his wounds after a battle.